Implementing NCSC import patterns on a budget

Recap

In my last article I wrote about making a firmware data diode from a £10 unmanaged network switch. The device itself works as a data diode, only allowing data through in one direction, which is great for certain situations such as:

Exporting data from a trusted network to an untrusted network through a data diode, assuming we don't mind the data we're exporting being out in the big bad world, eliminates the reverse path for anything malicious to go back into our trusted network. This example assumes the networks are otherwise air gapped.

What happens when we want to move data into our trusted network from the untrusted network? Well a data diode alone doesn't do much here, we still don't trust any data coming from the untrusted network. We have removed the possibility that should something malicious enter the network, at least it can't send anything, such as important data, back out the way it came in. That's not great, we can do better!

In this article we're going to look at how you might safely import a PDF file from the big bad world, into our lovely secure enclave.

But first you might have read the title and thought...

What is the NCSC?

The NCSC is the National Cyber Security Centre here in blighty. They produce guidance on how best to protect from all sorts of cyber threats, as well as providing reference architectures and patterns for building secure digital processes.

What is the Safely Importing Data Pattern?

The Safely Importing Data Pattern is an architecture provided by the NCSC on how to safely move data from an untrusted to a trusted network. As with all cybersecurity patterns it doesn't guarantee safety, it just makes it significantly harder for an adversary to exploit or attack it.

There's some funky new terms you might not have heard of in there, so lets break it down...

What is a transformation engine?

Something that transforms a file or content into another format, pretty simple? But why...

When dealing with complex data types, like a PDF for example, there are many nooks and crannies to hide malicious data in. This makes it more difficult to reliably check for malicious intent, if the data was in a simpler format it's much easier to check.

In our PDF example, we might not care about all the gubbins that can be expressed in the PDF format we might just want the text inside. So our transformation engine might simply take PDFs, and spit the text content out. As it happens there are a number of tools that can do exactly this, which we'll cover later.

What is a protocol break?

A protocol break means terminating a network connection and its associated network protocols and then rebuilding it and sending it on. But why...

It might seem redundant to terminate and reconstruct a connection and network protocols, but again it is about reducing the attack surface. Standard OS network stacks consist of vast amounts of code, parsing all sorts from ARP, ICMP, DHCP etc. The more complexity, the more places vulnerabilities can hide. By terminating and reconstructing connections we can throw away protocol headers that might look to exploit these vulnerabilities. If we're deliberate in extracting the payload, then pass it onwards with protocol headers that we control, we reduce the risk protocol-level exploits are propagated.

What is a verification engine?

Something that verifies data, but you might be wondering what do you mean verify data?

Syntactic verification

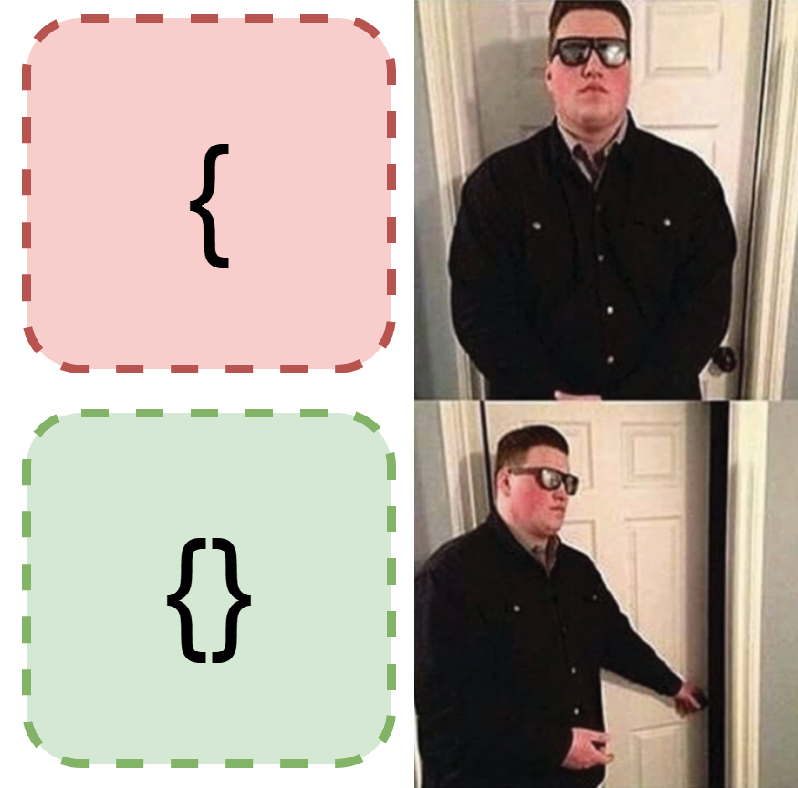

One type of data verification is called syntactic verification, which is about verifying the syntax of data. I find an example is the easiest way to explain this, let's take JSON as an example:

{}is a valid bit of JSON. Why? Because it conforms to the JSON syntax, it's an empty JSON object.{is not valid JSON. Why? Because it doesn't conform to the JSON syntax, it is missing a closing brace.

That's the long and short of it, if data matches the expected syntax it's syntactically valid.

The follow-on question is how can we check that a piece of data matches the expected syntax? That largely depends on the type of data you're trying to verify, for our JSON example you could use any of the following popular libraries:

- Python json

- Rust serde_json

- C++ nlohmann/json

There are some more universal ways of describing and therefore verifying syntax, such as ABNF schemas, I don't think we need to go over those!

Semantic verification

Another type of data verification is called semantic verification, which is about verifying the semantics of data. Semantics means the meaning of something, but what does that mean in the context of data? Again, lets go for an example to explain this, let's imagine we're dealing with data coming from a plane:

{

"elevation": 200,

"pitch": 1,

"yaw": 10

}

In this example the plane might have some sensors recording this information, and might be sending the data to the black box or to ground control.

So what would make the example data above invalid semantically?

{

"elevation": "cheese",

"pitch": 1,

"yaw": 10

}

Well this is clearly wrong, elevation can't be cheese. It's still valid JSON, it's just not valid plane data.

{

"elevation": 200,

"pitch": 1

}

This example might be wrong, it depends on whether yaw is a required field. Well who decides that? Whoever made the two systems this data is travelling between will have been in agreement on what data must be included and what it means. And how do they define this agreement? Typically, via a schema.

That's probably enough explaining for now, let's have a look at...

What are we going to import?

We're going to be importing PDFs through JSON, and then reconstructing the JSON back into a PDF on the trusted network.

The approach

The initial architecture is outlined below:

Comprised of two components our modified LS1005G and a new recruit, the NanoPi R2S.

1 - PDF to JSON

This is our transformation engine. We're going to do something simple to start with and only extract the text and the filename, to do this we're going to use pdfplumber.

$ python3 pdf_to_json.py example.pdf

{"filename": "example.pdf", "text": "this is the pdf text!"}

We can send then send the JSON content of the PDF over UDP at the ingress of the NanoPI R2S.

$ python3 pdf_to_json.py example.pdf | nc --udp 192.168.50.1 5005

2 - Protocol break receiver

Wait a second you say, shouldn't we have a protocol break sender first? You're right - however; we need to drop and ignore all of the protocol headers we don't care about here - UDP headers, IP headers and the Ethernet frame. How are we going to do that? Using raw sockets we can evaluate and completely ignore any protocol headers down to layer 2 where an attacker might look to exploit.

We can do this using any of:

- Python scapy or socket.SOCK_RAW

- Rust pnet or nix

- C++ yes

Here is a "dumb" example that just jumps past protocol headers and prints the payload.

import socket

ETHERNET_HEADER_LEN = 14

IP_HEADER_LEN = 20

UDP_HEADER_LEN = 8

PAYLOAD_OFFSET = ETHERNET_HEADER_LEN + IP_HEADER_LEN + UDP_HEADER_LEN

def start_raw_socket():

try:

socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.ntohs(0x0003))

except PermissionError:

return

while True:

raw_data, addr = socket.recvfrom(65535)

if len(raw_data) > PAYLOAD_OFFSET:

payload = raw_data[PAYLOAD_OFFSET:]

if payload:

print(f"{payload}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

start_raw_socket()

3 - JSON validation

Great we've not got the payload extracted from the raw packets and binned the other protocol information, we now need to do our syntactic and semantic validation. This is our verification engine. This is really the easiest bit due to sheer number of ways of handling JSON in most languages. For syntactic validation we simply attempt to parse the incoming JSON using:

- Python json

- Rust serde_json

- C++ nlohmann/json

For semantic validation we compare the parsed JSON against a JSON Schema using:

- Python jsonschema

- Rust jsonschema

- C++ json-schema-validator

An example JSON Schema for our PDF example might look as follows:

{

"type": "object",

"additionalProperties": false,

"required": ["filename", "text"],

"properties": {

"filename": {

"type": "string",

"pattern": "^.+\\.pdf$",

"maxLength": 255

},

"text": {

"type": "string",

"pattern": "^[\\x00-\\x7F]*$",

"maxLength": 10000

}

}

}

This schema says for the JSON to be semantically valid:

- It must be an object

- It must only have the fields "filename" and "text"

- The "filename" field must have a value of type string, matching the regex and of max length 255

- The "text" field have a value of type string, matching the regex and of max length 10000

If you're thinking, well what if the library has a vulnerability? Good instinct! One way around that is design your own parser and make it handle as little context (aka 1 byte) as possible at a time, but ain't nobody got time for that. If you do have time for that, look at stuff like nom.

4 - Protocol break sender

We've now got our syntactically and semantically valid JSON, now all we need to do is shove some UDP headers back on it and blast it at port 4. Again, plenty of options for sending UDP:

5 - JSON to PDF

Nearly there! Final step we now need to take our JSON containing PDF file name and text and spit out a PDF on the destination system. For this task we can use something like fpdf2.

Keep it simple stupid

The design above is built using a £10 network switch and a ~£40 NanoPI R2S. We could make the whole device a lot cheaper and more simple if we didn't need to use the NanoPI R2S. We do however need a device for our syntactic and semantic verification, as well as our protocol break. To cut the cost, what if we could use a device with a less powerful core and a single ethernet port? Enter the...

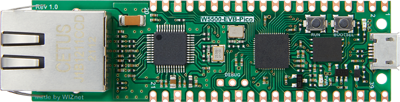

W5500-EVB-Pico

Only £10, but only one ethernet port. How would that work?

By configuring the switch to allow port 1 to only communicate with port 2, port 2 only to port 3 etc we end up with a daisy-chain of diodes.

Assuming each of the devices 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 are on unique IPs we have a setup where a packet leaving device 1 can only reach device 2, a packet leaving device 2 can only reach device 3 etc. Now we only need a device with a single ethernet port to add new features in our daisy chain! This also means we can use up to 3 devices for validating, transforming or whatever we want. Let's see what the architecture looks like using a single W5500-EVB-Pico.

This is also a useful iteration in that it massively simplifies the complexity of the device, from a general-purpose Linux board in the NanoPi R2S to a microcontroller only handling a specific task we are reducing the surface area for exploitation.

Firmware

For the W5500-EVB-Pico firmware I used embassy and specifically embassy-net-wiznet. As previously discussed, I used raw sockets to receive datagrams directly off the wire and bin all the protocol information. As this device operates in a Rust no_std environment I needed to find an alternative to serde_json for syntactic validation of JSON. Lucky for me, there is a crate serde-json-core for this express purpose. Anyway, if you want you can check out all the source code for this part of the project here:

Conclusion

This is by no means a comprehensive implementation of this pattern, and there is several ways it could be improved, but it aims to explain and demonstrate the different stages of a high-assurance data import pattern. By binning protocol headers, enforcing strict schemas and segmenting networks with cheap data diodes we can build a robust defence against attackers importing malicious data and compromising our trusted network.

If you are interested in replicating this setup, adapting the firmware for different data types, or discussing how these patterns apply in fields like industrial IoT, feel free to reach out!

Future ideas

Whilst exploring the settings available in modifying the switch I found port mirroring as a configurable option per port. You can configure port mirroring per port for both RX and TX packets, as an example you could have all RX packets arriving at port 1 be mirrored from port 4. So how can we use this to make the process even safer?

1 - Transformation engine

As previously described.

2 - Mirror port 1 RX packets to port 4

Now we have the exact same packets arriving at both NanoPI R2S's.

3 + 4 - Separate network and JSON verification stacks

Each NanoPI R2S is running a separate network and JSON verification stack, one might be lwIP, one might be Linux for instance.

5 - AND check

If both verification stacks agreed that the packet was syntactically and semantically correct we allow that packet to pass.

Why?

With this pattern, we are making it significantly more complex for an attacker to exploit a vulnerability in one verification stack, as each packet is mirrored and passed through both stacks simultaneously.